Market anniversary and changes in my inflation views

IMPORTANT ANNIVERSARY

During the first quarter of 2017, an important anniversary passed without much fanfare: it has now been eight years since major US equity markets bottomed (Friday 6-Mar-2009).

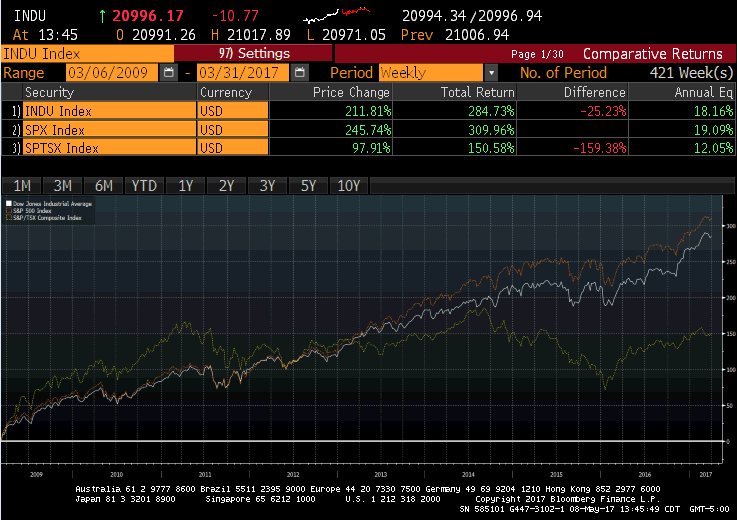

Starting the following Monday, after then-Fed Chairman Bernanke announced unwavering Fed support for securities markets, markets are up around 300% (see chart 1 below). The subsequent eight years have marked one of the longest running bull markets in history. Yes, there have been minor corrections along the way (like the Taper Tantrum of May-June 2013 and the Flash Crash of 2015) but in general, markets have remained on a steady upward trajectory.

Chart 1: Index returns 6-Mar-2009 to 31-Mar-2017

At Anson Funds, the investment management firm that my partners and I run, we continue to live and work and invest and trade in the same world that changed so dramatically eight years ago. Moreover, while the Fed has officially ended QE and has started the process of actually raising interest rates again, two major foreign central banks (the ECB and BOJ) continue to inject liquidity into markets on an ongoing basis via large scale asset purchases.

Like any purchases, those actions work to drive up asset prices. And, in the case of bonds, higher prices also mean lower yields (and hence, lower interest rates). So, although major global equity (and bond) markets remain strong, there is no denying that major central banks are large players in these markets, pushing up prices.

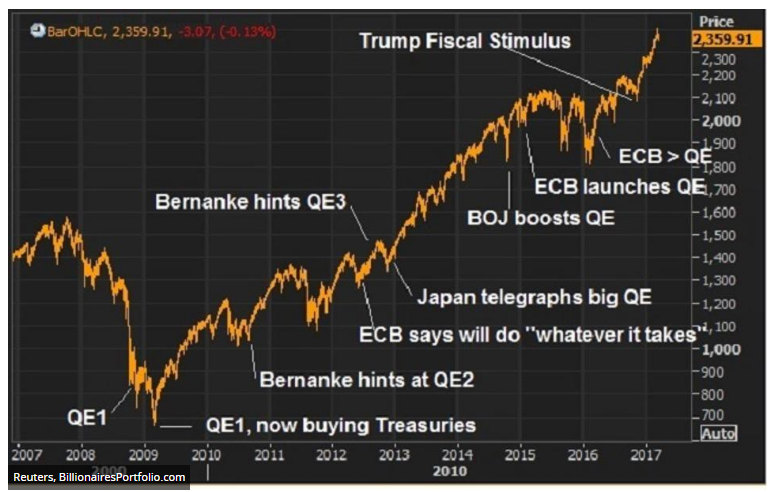

Chart 2 is taken directly from a March 2017 Forbes article excerpted below. It clearly shows when the various forms of QE (both U.S. and foreign) were announced and implemented, and the effects of those QE programs on the S&P 500.

Chart 2: QE around the world – 2008 through early 2017

Excerpt from Forbes article:

First, why did stocks (the S&P 500) turn at 666 on March 9, 2009?

Policymakers were scrambling to stop the bleeding in banks, trying to unfreeze global credit and stop the dominoes from continuing to fall.

The Fed had already launched a program a few months earlier to buy up mortgage-backed securities, to push down mortgage rates and to stop the implosion in housing. Global central banks had already slashed interest rates in an attempt to stimulate the economy. The U.S. had announced a $787 fiscal stimulus package a few weeks earlier. And then finance ministers and central bankers from the top 20 countries in the world met in London on March 14. Here’s what they said in the opening of their communique:

We have taken decisive, coordinated and comprehensive action to boost demand and jobs, and are prepared to take whatever action is necessary until growth is restored.” The key words here are “coordinated” and “whatever action is necessary.”

The Fed met four days later and rolled out bigger purchases of mortgages and for the first time announced they would be buying government debt. This was full bore QE. And it was with the full support of global counterparts—that later followed.

What wasn’t known to that point was to what extent policymakers were willing to intervene to avert disaster. This statement by G20 finance heads and the action by the Fed let it be known that all options were on the table (devaluation, monetization, etc)–and they were all-in and all together in the fight to stave off an apocalypse. With that, the asset reflation period started. And it started with QE.

A NEW UNDERSTANDING OF EXCESS RESERVES AND OUTLOOK FOR INFLATION

I have recently been spending a lot of time reading about a topic that has bothered me for eight years now—the issue of expected US dollar inflation resulting from the dramatic growth of excess reserves at the Federal Reserve (and similar balance sheet expansions at other major central banks).

While my partners and I had many internal debates on the issue, we eventually settled on our own consensus view. We decided that the growth of central bank balance sheets, (as reflected by the growth in excess reserves), were a plainly visible indicator that monetary inflation was looming on the horizon.

Clearly things have not turned out that way.

It seems that I missed something important in my analysis and thus my views have since evolved. My current understanding has developed thanks mainly to the works of Zoltan Pozsar[i] at Credit Suisse and Professor Perry Mehrling[ii] at Barnard/Columbia. Pozsar and Mehrling (and many others) have pointed out that the collapse of the Shadow Banking system during the 2008 financial crisis has led to the Fed and other central banks moving from ‘lender of last resort’ to ‘dealer of last resort‘, essentially backstopping many of the financial instruments used in money markets, asset-backed securities, and derivatives.

In addition, dramatic regulatory changes brought about by Basel III and Dodd-Frank essentially mean that all those ‘excess’ reserves at the Fed are actually ‘required’ reserves. Since all U.S. banks and U.S. branches of foreign banks now have to hold the highest quality assets as reserves against short term liabilities, and the highest quality assets of choice are reserves at the Fed, and reserves at the Fed earn interest (IOER[iii]), far more reserves are REQUIRED in 2017 than were required in 2008. Thus, the massive balance sheet at the Fed is not a sign of pending inflation; it is merely the ‘new normal’ given regulatory constraints and the plumbing of the international banking system.

I do not plan to suddenly become a macro trader; I continue to select investments for our funds based on fundamental, bottom up analysis. However, my views on these big picture questions do inform how I view and evaluate the investment opportunities out there. The reality is that all of us in the investment management business are operating in a world that is completely new.

Central banks have never before played such a direct and prominent role the investment arena before. Since 2008, the world of central banking has clearly changed in the developed economies. We are all students of this brave new world together, and we are all trying to understand the implications of the new regulatory and policy environments that we now find ourselves in.

NOTES

[i] Zoltan Pozsar, Credit Suisse Economic Research. “Global Money Notes #5: What Excess Reserves” 13-Apr-2016, http://bit.ly/2pZFLoM

[iii] IOER: Interest On Excess Reserves, currently 50 bps